• When evidence hurts: cognitive dissonance and statistical thinking

Cognitive Dissonance

Table of Contents

- Context

- Defensive strategies against cognitive dissonance

- The information cycle (or dissonant process)

- Statistical thinking as an antidote

- Countermeasures: the war against coherence

- Current cases and examples: strategies

- Sources and recommended reading

Since I started as a programmer, I used to interact with very different profiles to debate monolith vs. microservices and synchronous vs. queues. In those discussions I came across the concept of “cognitive dissonance”. The first thing I thought was: “this doesn’t happen to me; I base myself on data”. Nothing could be further from the truth.

As I delved deeper into what dissonance implied, I intuitively began to make calibrations like: “I’m 80% sure about X”, “I’m 95% sure about B”, and I started incorporating range calibration — using bands: 40-60 uncertain, 60-80 probable, 80-95 very probable.

Shortly after, I reviewed what had happened after each meeting; believing myself free from all dissonance, I fell for it multiple times. Even so, I kept managing that tendency, because it’s intrinsic to how our brain works and is nothing more than another survival mechanism; what I started applying didn’t eliminate the friction, but it improved the expected cost of a bad decision.

Two paths when facing conflict between ideas

1. Context

- Cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957): when two cognitions clash, psychological tension arises and a search for coherence that we try to satisfy (by changing beliefs, seeking selective support, avoiding dissonant information).

- Brain, culture and symbols (Bartra): the mind doesn’t live isolated in the skull; it relies on symbolic systems and external supports (exobrain). Evidence evaluation is a cultural practice, not just neuronal.

- Current problem: we are surrounded by contradictory information — often of low reliability — that resonates with our internal coherence, plus echo chambers and rationalizations.

2. Defensive strategies against cognitive dissonance

One of the most revealing texts I read was A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, by Leon Festinger.

It allowed me to understand how a new idea, which somehow contradicts our previous beliefs or assumptions, can generate deep discomfort: it challenges us because it threatens the internal coherence with which we sustain our worldview.

Faced with this discomfort, we usually activate a series of defensive strategies. They are mental mechanisms that help us reduce tension without having to review what we believe. Some of them are subtle; others, radical.

Let’s look at some of the most common ones:

-

Reinterpretation: we modify the terms or context of the new information so that it can fit into our belief system, without touching the core of what we already believe.

“When he said talent doesn’t matter that much, he surely meant extreme cases.”

Observable signals:

- Definition changes a posteriori (“by talent he meant discipline”).

- Softening qualifiers: “actually…”, “in this context…”.

- Ad hoc exceptions added after seeing the data.

- Relabeling evidence: “it’s not a failure, it’s expected behavior”.

- Framework changes (population/reference case) during discussion.

-

Source devaluation: we apply an ad hominem fallacy: instead of analyzing the argument, we attack the person making it. We question their authority, intention, or even character, in order to keep our ideas intact.

“What does he know? He hasn’t even worked in the sector.”

Observable signals:

- Asking first who says it before what data they present.

- Selective credentialism (demanding credentials from some but not others).

- Attributing intention/agenda (“they’re here to sell us X”) instead of evaluating evidence.

- Accepting/rejecting the same argument if said by someone from the group and rejecting it if it comes from outside.

- Citing irrelevant past errors to dismiss the current argument.

-

Selective search (confirmation bias): we only expose ourselves to information that reinforces what we already think and avoid data that could contradict it. We live in a cognitive bubble.

“This article says exactly what I’ve always defended. I don’t need to read the other one.”

Observable signals:

- Homogeneous feeds/reading lists; unfollowing dissonant sources.

- Closing “opposing” tabs without reading or with superficial reading.

- Bookmarks/Notion/RFCs only with aligned pieces; no counter-evidence.

- Experiments designed to confirm, not to falsify hypotheses.

- Meetings where the critical/affected party is not invited.

-

Avoidance: we directly disconnect from the topic. We avoid news, conversations, or environments that could trigger dissonance. The more threatening the information seems, the greater the desire to avoid it.

Observable signals:

- Changing the subject when uncomfortable metrics appear (churn, p95, 5xx).

- Postponing reviews/retros with counter-evidence sine die.

- Canceling interviews with critical users; “no time for research”.

- Disproportionate emotional reactions to contradicting data.

- Systematic “I’ll look at it later” regarding reports that don’t fit.

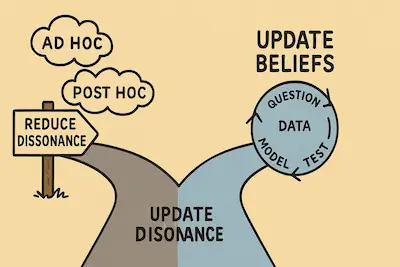

3. The information cycle (or dissonant process)

Information cycle

I’m fascinated by how our mind works, especially when it faces new information. We can think of information not as neutral data, but as something that goes through a psychological cycle: before we’re exposed to it, during its processing, and after consuming it.

At each stage, our biases and cognitive defense mechanisms activate a tension between coherence and discomfort.

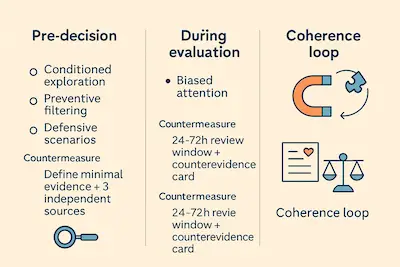

Before receiving it: anticipatory filtering

We live exposed to an infinity of stimuli. But we don’t process them all equally. In fact, we tend to filter in advance information that we intuit as dissonant.

- We prefer headlines that sound coherent, even if the source is dubious.

- We actively ignore what could shake our certainties.

- We seek, without realizing it, to confirm what we already believe.

The information that never reaches us is, many times, the most necessary for growth.

Signals: headlines “that fit”, blocking dissonant sources, homogeneous lists. Action: Rule of 3 sources before forming an opinion. Ritual: checklist: independence / method / format.

While consuming it: biased attention

- We pay more attention to arguments that reinforce what we already think.

- We quickly dismiss ideas that make us uncomfortable.

- We judge the source if what they say doesn’t fit our narrative.

We’re not trying to understand: we’re trying to confirm.

Signals: you highlight confirmations, quickly dismiss the uncomfortable, you go to the “who” before the “what”. Action: double column resonates (1-5) / is reliable (1-5), integrate only if ≥3/5 in both. Ritual: steelman of the opposing argument in 3 bullets before deciding.

After consuming it: cognitive closure

Once exposed to information, the last stretch of the cycle is activated: assimilating it without destabilizing our identity.

Here three common mechanisms appear:

-

Premature closure: we remember only what confirms our ideas; counter-evidence is ignored or relabeled as “isolated case”.

-

Commitment escalation: after publicly committing to an idea, changing it becomes harder because we’ve already invested reputation.

-

Retrospective rewriting:

“I already knew this, I just hadn’t said it that way.”

It generates retrospective coherence, but impoverishes learning: if you “already knew it”, you never change anything.

Signals: you remember only confirmations, move criteria after seeing results, post hoc narrative. Action: before/after log + if-then rules + cognitive stop-loss (when to revert). Ritual: record: date - signal - adjustment - new probability range.

This processing bias explains why two people can read the same article and reach opposite conclusions. To avoid it, we install control gates at each phase.

4. Statistical thinking as an antidote

The purpose of an information exchange, whether through a conversation or an exhaustive search, is not to win or “be right”, but to improve our model of reality: reconciling what we already believe (internal coherence) with what the data, experience, or context show (external world). You’ll see 2-3 micro-rituals applicable today.

In practice we have three steps

- Evaluate an idea on two axes:

- Fit with your framework (1-5: 1=breaks, 3=mixed, 5=reinforces).

- Reliability of the evidence (1-5: 1=rumor, 3=preliminary data, 5=independent convergence).

- Decide:

- Integrate if reliability≥3/5 and fit≥4/5 (e.g., solid data and clear coherence improvements).

- Park/provisionally refute if reliability greater than 3/5 or fit=1/5, even if it “resonates”.

- Update your framework: leave a trace of what changed and why.

- Log (minimum format): date - signal - decision - if-then rule - new range (%).

When we’re in the middle of a conversation, consuming content, or trying to reach an agreement, it’s worth remembering that thinking doesn’t have to be dichotomous, even if it generates discomfort: an argument can have degrees of certainty and incorporation into our belief system. For example: 70% that the meeting will be useful; if we send agenda and objectives 24h before → +10 pp; if there’s no moderator → -10 pp.

We could express this belief we’re exposed to in four intervals 0-25% very unlikely, 25-50% unlikely, 50-75% likely, 75-100% very likely instead of accepting or discarding it, so that argument won’t be eliminated but will have a determined weight.

We can use this strategy to justify our belief and maintain coherence between ideas. However, without prior rules, the bands become performative: they end up defending a position instead of favoring learning.

In any case, these degrees can change the certainty interval: if X occurs, argument A will rise 10% and move to the “likely” interval.

Even adopting the degree system, we can force the system to still keep our beliefs intact:

- Inflate/deflate scores without basis (adjusting them up or down to match our own thesis).

- Compare the idea with extreme or non-representative cases to reduce its weight. Countermeasure: fix population, window, and metric before evaluating (prior criteria in writing).

- Log of expected cost (impact × probability) of adopting/rejecting the novelty and of decisions we’ve been making; record: date - signal - decision - if-then rule - new range (%).

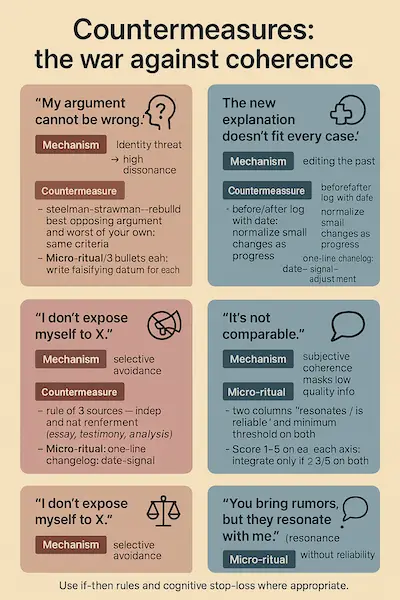

5. Countermeasures: the war against coherence

-

“My argument can’t be wrong.” Mechanism: threat to identity → high dissonance → rationalizations (“the source fails”, “that case doesn’t count”). Countermeasure: steel and straw (steelman / strawman): reconstruct the best opposing argument and the worst of your own, and judge them with the same criteria. Ritual: write in 3 bullets the rival steelman and in 3 bullets your strawman; decide what data would falsify each one.

-

“The new explanation doesn’t fit all cases.” Mechanism: fit perfectionism; a local counterexample triggers global dismissal. Countermeasure: conditionalize: make explicit where yes / where no; draw an if-then map with validity limits. Ritual: 3 rows: “if [condition] → applies / doesn’t apply / requires adjustment”.

-

“I already knew that.” (retrospective rewriting) Mechanism: editing the past to preserve temporal coherence. Countermeasure: before/after record with date; normalize small changes as progress, not defeat. Ritual: one changelog line: date - signal - adjustment - new range/thesis.

-

“I don’t expose myself to X.” (echo chamber) Mechanism: selective avoidance to reduce dissonance. Countermeasure: rule of 3 sources: at least three independent and of different formats (essay, testimony, analysis). Ritual: checklist: 1) independence, 2) explicit method, 3) different format.

-

“It’s not comparable.” (ad hoc exception) Mechanism: moving the comparison criteria as convenient. Countermeasure: equal / similar / different matrix + fixed criteria defined before the case. Ritual: define 3 criteria (e.g., population, metric, time window) and classify the case in the matrix.

-

“You bring rumors, but they fit me.” (resonance without reliability) Mechanism: subjective coherence masks low information quality. Countermeasure: double column “resonates / is reliable” and minimum threshold in both to integrate an idea. Ritual: score 1-5 on each axis; only integrate if ≥3/5 in both.

6. Current cases and examples: strategies

Common objective: transform the dissonance originated by contradictory information (often unreliable) that resonates with our coherence into more solid decisions through coherence rituals (precommitments, rival stories, before/after updates, double column resonates/reliable), without depending on metrics or dashboards.

Experiments with useful friction in product

-

Precommitment: formulate the decisive question and the if-then: “If we observe signals (S1 and S2) (qualitative and traceable), we integrate the novelty; if (R1 or R2) appear (risks/damage), we revert”.

- e.g.: If (abandonment in “verification” drops 20% relative in 2 sprints and 5/10 interviews mention less confusion) → integrate; if (tickets “I don’t understand verification” ≥5/week for 2 weeks or error rate >1% per transaction for 7 days) → revert.

-

Rival stories: write the best version of the argument for and against; before debating, fix in writing symmetric criteria for both (e.g., population, metric, time window, success threshold, review horizon, acceptable risks).

-

Activation signals (non-numeric): examples of user behaviors, support objections, narrated abandonment patterns, recurring frictions in interviews.

- Users say “I don’t understand verification” when abandoning that step.

- In support “I can’t find where to change my password” appears repeatedly.

-

Review window: fixed date (e.g., 2 weeks) to evaluate before/after in writing.

Blameless post-mortems

- Plane separation: (a) what changed (narrable/traceable facts); (b) why we decided that way (context/limitations); (c) what to update (rules, term dictionary, if-then criteria).

- Counter-evidence record: list of pieces that don’t fit but could indicate learning; assign follow-up owners.

- Update language: “In light of X and Y, we update Z; if W appears, we review again”.

Architecture decisions

- Dissonance risk: the option that resonates with the team’s identity (“we’re microservices” / “here everything is synchronous for simplicity”) can prevail despite contradictory signals from the context.

- Ritual: RFC with steelman of the discarded alternative; invariant criteria defined before debating (real coupling, domain boundaries, delivery rhythm, operational capacity, failure radius, end-to-end latency). Precommitment with if-then map and cognitive stop-loss.

- S signals (integrate): fewer handoffs between teams, simpler deployments, stable context boundaries, less coordination for small changes.

- R signals (review/revert): dependency creep, failure cascades, increasing coordination for small changes, proliferation of ad hoc exceptions.

Backlog prioritization with contradictory signals

- Case: “this feature is key for enterprise” (rumor that fits but is unreliable).

- Ritual: rule of 3 sources (sales, support, user research) + quick interviews (5 clients) with steelman of the objection; minimum viable counterfactual: what happens if we don’t do it for 2 sprints?

- Conditional decision: if S1/S2 appear (narrated abandonment patterns, repeated traceable objections), integrate; if not, postpone and review date.

Code review: identity preferences vs. technical criteria

- Risk: confusing taste with criteria (e.g., framework style vs. clarity/security).

- Ritual: PR template with three blocks: (a) adverse risk contemplated, (b) what would change my opinion, (c) steelman of the alternative. Statement traffic light (green=traceable fact, amber=inference, red=rumor/baseless coherence). Double column resonates / is reliable.

7. Sources and recommended reading

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957).

- Bartra, R. Anthropology of the Brain: Consciousness, Culture and Free Will (2014).

- Gelman, A. & Loken, E. The garden of forking paths (essay on analytical decisions and significance).

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow (practical insights on biases and uncertainty).

- McElreath, R. Statistical Rethinking (applied and explicit approach on uncertainty and updating).