• A reflection on stability, performance, and what I learned connecting Maslow's pyramid with Hawkins' map of consciousness

Maslow and Levels of Consciousness: When the Foundation Fails

Table of Contents

- Maslow’s Pyramid

- Map of Consciousness (David R. Hawkins)

- Maslow & Hawkins: The Connection

- Key Differences

- A Practical Way to Use Them Together

- Reflection

I’ve been reflecting for a while on the importance of a certain degree of stability at work. It’s a prerequisite: it not only allows us to produce more, but to sustain something resembling personal fulfillment… even if just for a time.

This reflection appeared without warning. It’s curious how our mental processes work: certain ideas aren’t “decided,” they irrupt. As if someone entered a dark room with a torch and, when illuminating, didn’t always bring good news. At that moment in my career, the torch pointed at something uncomfortable: I had entered a position where, from the beginning, I didn’t quite fit.

I was transparent from day one, but I still began to perceive a subtle and constant friction: conversations that didn’t flow, diffuse expectations, a discomfort that seeped into the everyday. As weeks passed, it became more evident: it wasn’t an environment conducive to growth, neither as a professional nor as a person. That point was the prelude to something more intense.

And when I say “intense,” I mean it seriously—perhaps I’ll go into more detail another time—because it was hard, difficult, and at the same time tremendously instructive. In a short time, I didn’t grow: I fell. It wasn’t a heroic tale or an epic of overcoming: it was a reduction of the system to minimum operating capacity.

I fully entered a process of hormesis: one of those episodes that expose you enough to force you to adapt. The curious thing is that my reaction wasn’t epic or particularly “heroic”; it was almost meme-like, automatic, as if my mind had activated a basic survival protocol. And precisely because of that, it was so interesting: because it allowed me to observe myself more clearly, understand my mechanisms, my limits, and my patterns under pressure.

And that’s when I understood something key: performance doesn’t fail due to lack of willpower; it fails when the environment pushes you to live in survival mode.

To go into more detail, I bring two frameworks that have helped me organize this intuition: Maslow’s pyramid and David R. Hawkins’ map of consciousness.

1. Maslow’s Pyramid

Source: Wikipedia

Maslow’s Pyramid (or hierarchy of human needs) is a psychological theory proposed by Abraham Maslow (1943). It suggests that our motivations are organized in levels: we tend to cover basic needs first, and as they are reasonably satisfied, “higher” needs emerge.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

The 5 Classic Levels

- Physiological: survival and homeostasis (breathing, eating, drinking, sleeping, etc.).

- Safety: feeling protected (health, resources, housing, stability).

- Social / Belonging: connection and bonds (friendship, partner, family, acceptance).

- Esteem / Recognition: self-esteem and external recognition (competence, achievements, reputation, status).

- Self-actualization: development of potential and life meaning (Maslow also calls it growth motivation or “being needs”).

Maslow distinguishes between deficiency needs (the first four; when lacking, they strongly drive behavior) and self-actualization as a growth need.

Metaneeds and Metapathologies

At the top, Maslow speaks of metaneeds (values like truth, beauty, justice, etc.) and suggests that if frustrated, metapathologies can appear (e.g., cynicism, depression, alienation).

Key Ideas and Critiques

- A central idea of the model is that unsatisfied needs influence behavior more; satisfied ones lose motivating power.

- There are also critiques: research reviews have found little evidence of a rigid universal hierarchy, and alternative models are mentioned (e.g., Max-Neef).

2. Map of Consciousness (David R. Hawkins)

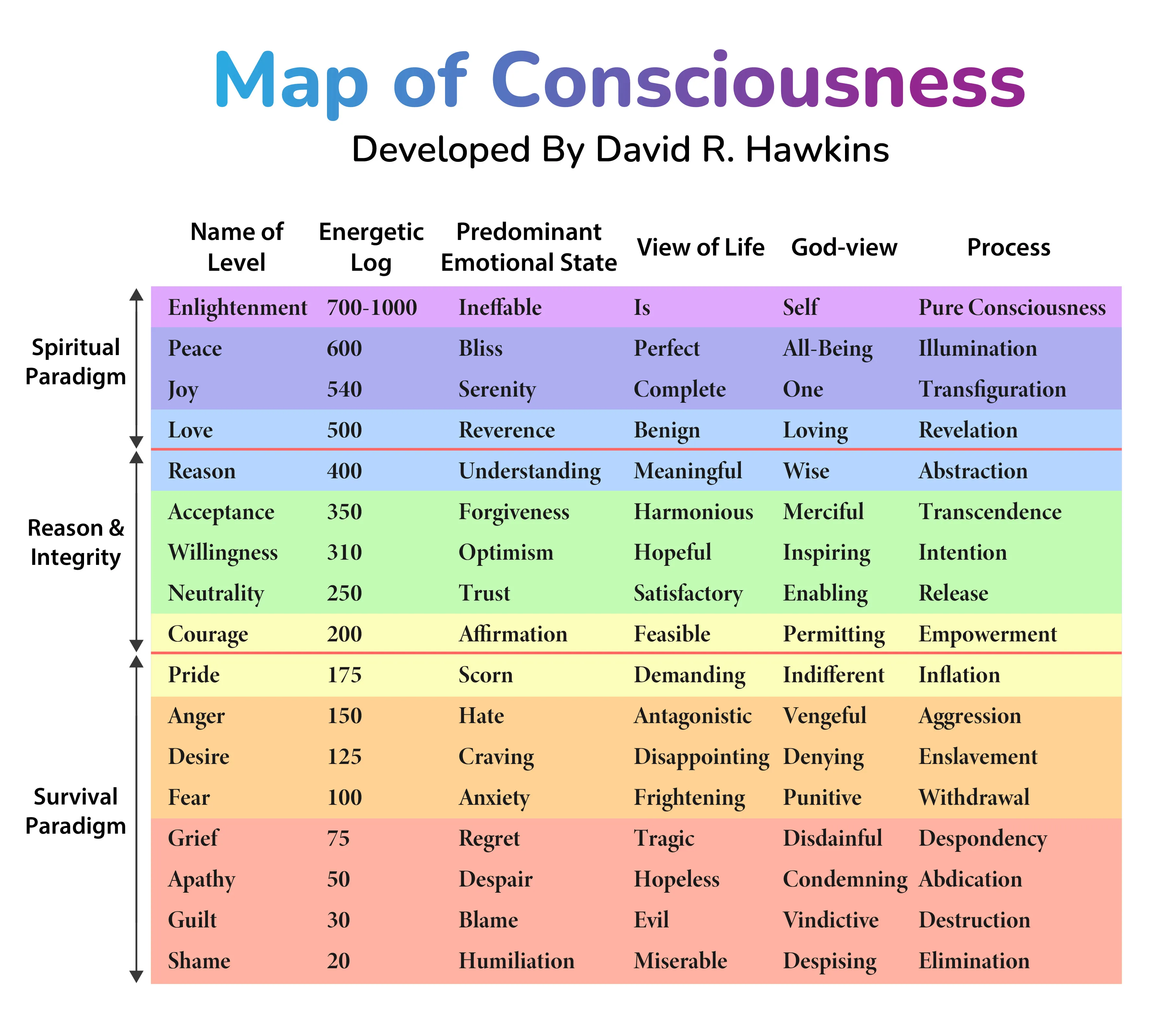

David R. Hawkins’ Map of Consciousness (popularized in Power vs. Force) attempts to order human states—emotions, attitudes, and “worldview”—on a logarithmic scale from 1 to 1000. The premise is that each state “calibrates” at a level, and crossing certain thresholds implies a notable change in how one perceives and interprets reality.

Hawkins’ Levels of Consciousness

Key Thresholds Proposed by Hawkins

- 200 (Courage): “turning point” between reactive/defensive states and more constructive ones (“force” vs “power”).

- 500 (Love): marked emotional openness; paradigm shift toward compassion and connection.

- 600+ (Peace) / 700+ (Enlightenment): levels linked to mystical experiences or spiritual realization.

Key Ideas of the Model

- The map describes a predominant state, not a momentary emotion: you can feel fear or sadness temporarily without that “redefining” your stable level.

- Hawkins maintains that the scale is logarithmic: small numerical changes would represent large jumps in “power” within his framework.

- He proposes not to read it as “better/worse,” but as gradients of consciousness (paradigms), to avoid judgment and foster compassion.

How It’s “Measured” and Common Critiques

Hawkins claims these calibrations are obtained through muscle testing / applied kinesiology. This technique is controversial: there are double-blind studies and reliability research that question its validity/consistency for diagnostic decisions or robust inferences.

3. Maslow & Hawkins: The Connection

Discovering Hawkins’ levels of consciousness accelerated the writing of this post. I want to share an epiphany—or rather, a connection—between two frameworks that, although born from different places, fit surprisingly well when you look at them as a single tool.

Put simply: Maslow proposes a motivation theory based on needs (what you lack or what you’re trying to cover). Hawkins proposes a map of emotional state and interpretation (how you feel and what story your mind tells you about what’s happening).

Seen this way, Maslow explains the engine (the need) and Hawkins describes the filter (the state). And when you combine engine + filter, a very useful model emerges for understanding why, in certain contexts—pressure, uncertainty, conflict, lack of recognition—not only do our priorities change, but also our perception, our decisions, and our behavior.

When a basic need isn’t covered, it’s very common to fall into states like fear, desire, anger, or apathy (the “survival” zone in Hawkins). When needs are reasonably covered and there’s safety, connection, and meaning, courage, neutrality, acceptance, reason, love tend to emerge…

Physiology (Maslow) vs Shame / Fear / Desire (Hawkins)

If sleep, food, health, or energy are lacking… the body commands and the mind tends toward:

- anxiety, hopelessness, craving, irritability

- a “threatening,” “survival” view of life

Safety vs Fear / Anger / Pride

When there’s insecurity (money, stability, health, environment):

- Fear: hyperalertness, anticipation

- Anger: struggle for control

- Pride: “I can do it alone / I defend myself” (sometimes as armor)

Belonging (love/affiliation) vs Courage / Neutrality / Willingness

With a more stable base, the system opens up:

- Courage: moving from “it happens to me” to “I do something”

- Neutrality: less drama, more flexibility

- Willingness: cooperation, desire to contribute

Esteem vs Pride and Acceptance/Reason

Here there’s a key nuance:

- Pride resembles “esteem,” but it’s fragile and defensive.

- Acceptance and Reason are more like solid esteem: competence, judgment, self-control, responsibility.

Self-actualization vs Reason / Love / Joy

Self-actualization (Maslow) usually feels like:

- clarity, meaning, flow (Reason)

- connection and care (Love)

- serenity/joy (Joy)

4. Key Differences

To avoid mixing them incorrectly:

- Maslow is a psychological model (with critiques, yes, but useful).

- Hawkins proposes a “calibrated” scale and strong claims (kinesiology, etc.) that are not scientifically accepted. Still, as a metaphor for states, it can serve for reflection.

5. A Practical Way to Use Them Together

Think of two questions:

- Maslow: “What need is unmet right now?”

- Hawkins: “What emotional state dominates and what story is it telling me about the world?”

Example: if you’re in Fear, often the next step isn’t “think positive,” but to raise the base: sleep, minimal financial order, routine, social support, clarity of priorities. If you’re in Anger, there’s usually an unresolved need for control/safety/justice. If you’re in Pride, sometimes humility + openness is needed to jump to Courage.

6. Reflection

First Reflection

This model serves to estimate what level a person is at regarding their work. It’s a somewhat utilitarian view—I know—but the initial intuition came to me exactly from there: I wanted a simple framework to interpret behaviors, motivations, and blocks within the professional environment.

If you identify where someone is in their career (Maslow: dominant need) and the state from which they interpret reality (Hawkins: emotional filter), you can infer their most likely progression: what “next step” makes sense, what next higher level they can consolidate, or even what risk there is of regression if conditions change (stress, insecurity, lack of recognition, conflict).

This gives you a clearer view of the process they should follow:

- what they need to stabilize first,

- what levers unlock them,

- and what type of challenges or responsibilities are realistic without breaking them.

On a personal level, it’s also useful: you can see quite clearly where you are and what concrete movement brings you closer to the next level, instead of relying only on willpower or momentary motivation.

And finally, the framework suggests something interesting in leadership and management: it offers you a practical way to incentivize without forcing, aligning incentives and stimuli with the “next natural level.” You don’t motivate someone operating from safety and uncertainty the same way as someone already in esteem, autonomy, or meaning. In other words: the incentive isn’t just “more,” but “the right thing for the moment.”

Second Reflection

The second reflection comes from something I lived firsthand. Like almost everything in life, many variables intervene here, but there’s one idea that stuck with me: you can be at a “high” point on the pyramid and, due to an external or internal event, suddenly return to the base. And that return can be read in two very different ways: as loss or as opportunity.

For example, imagine you’ve been months in a stage of high performance (autonomy, recognition, purpose) and suddenly you’re reassigned to a project without visibility or your manager changes.

- Loss perspective: you interpret it as “I’m being demoted,” “I’ve lost status,” “I’m not worth it anymore,” and the focus goes to protecting yourself or regaining control.

- Opportunity perspective: you interpret it as “this forces me to rebuild from fundamentals,” “I can redefine priorities,” “I can train internal stability without depending on context.”

The event can be the same; what changes is the frame from which you process it. And that’s where this connection between Maslow and Hawkins starts to be really useful.

In any case, during that falling process, I realized something uncomfortable: how fragile our “truth” can be. No matter how much you try to “be yourself,” doing it consistently is harder than it seems, because we live within a social structure. Sometimes, when you’re at a certain level, you feel you have to fit in, regulate yourself, pretend a little, or move within an “acceptable average” to avoid a sudden fall. Not necessarily due to moral weakness, but for survival: when the environment fails, the system returns to basics.

And here an important nuance appears: the form of movement matters as much as the direction. If changes are progressive, the impact is smaller. If the fall—or the rise—is sudden, the psychological blow is much stronger.

Because any movement in both directions touches the ego:

- Downward, it can feel like sinking, loss of identity, shame, or fear.

- Upward, it can inflate the character: arrogance, rigidity, need to be right, dependence on recognition.

In both cases, when the change is abrupt, it rarely integrates in a healthy way. And for me, it was interesting to reach this conclusion: it’s not just about “climbing levels,” but how you transit them… and how much of your identity is tied to that level.